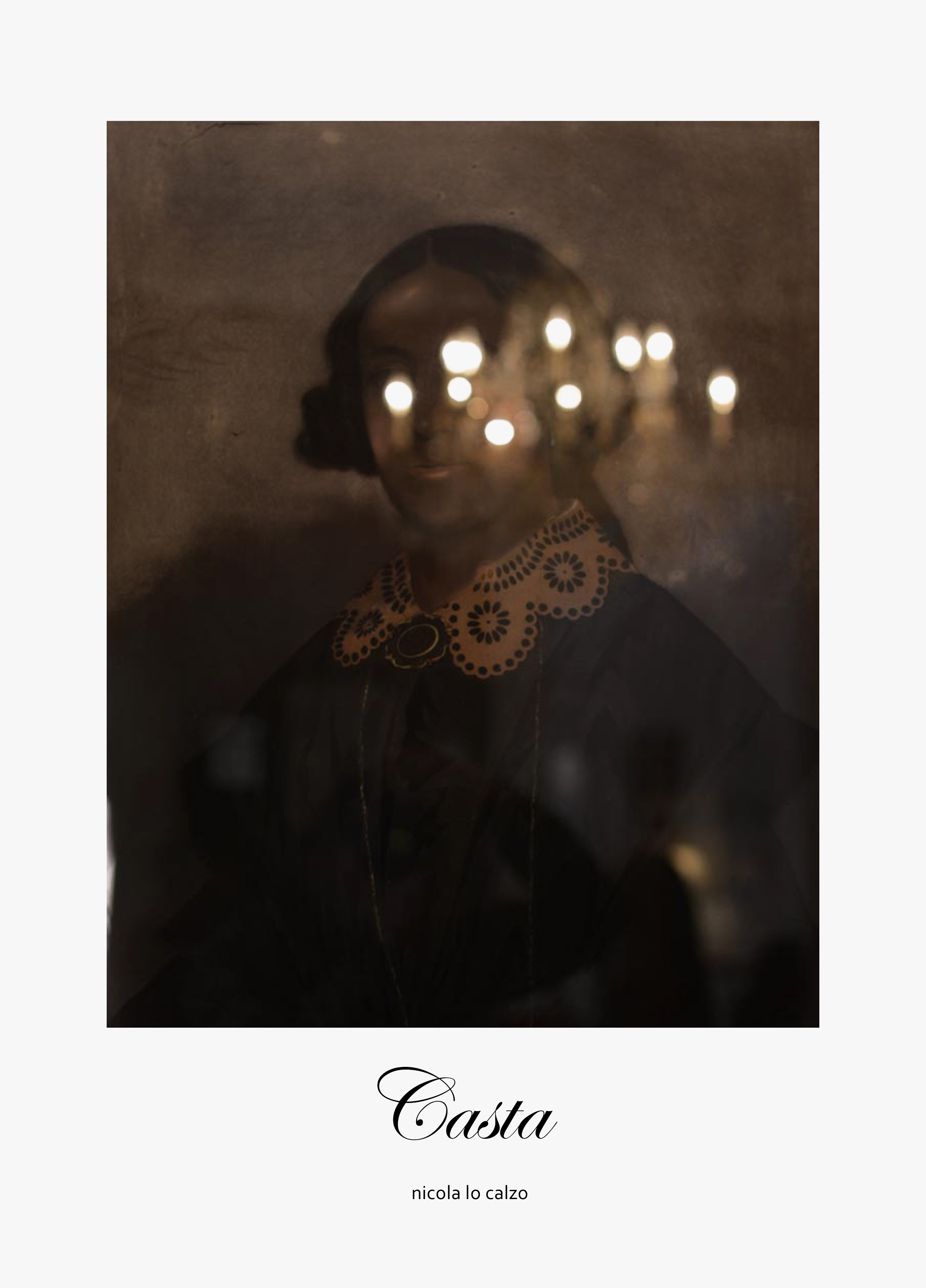

Casta: Race, Memory and Community in Southern United States

Intense emotions expressed around the world after the release of "Twelve Years A Slave" bears testimony to the significance of questions surrounding memory and race within the American society. The film, by British film director - Steve McQueen, strongly underlines the predicament of the legacy of slavery in the United States. Far from a done deal, this central element in the history of the United States of America remains a vivid subject, a century and several decades after its abolition. The passion aroused by the film reveals that while it is sometimes masked, restored or even reinterpreted, America's slave past is indispensable and remains at the heart of relations in the country. Alex Haley's "Roots", released in the 70's, prompted similar emotions and debates.

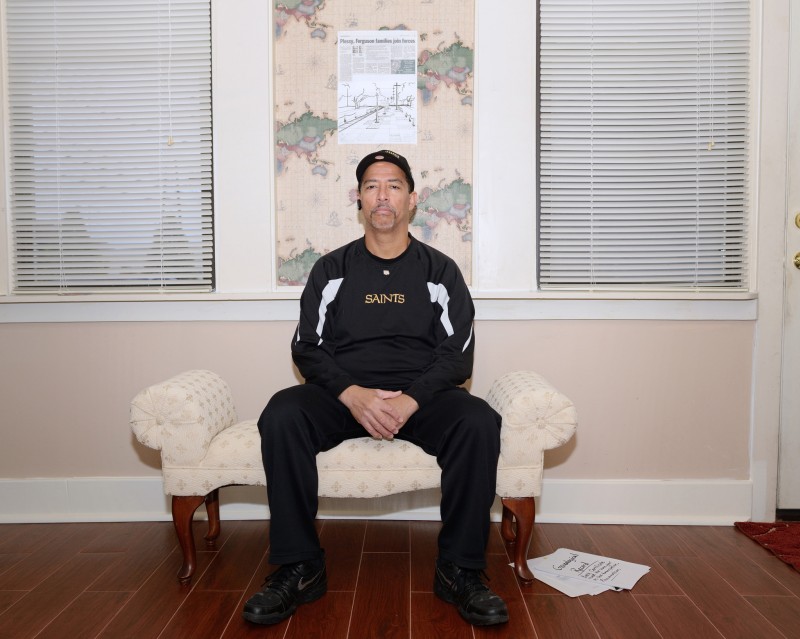

Aside from the neglect of African American communities, an underlying cause of the exponential increase of unemployment in New Orleans, the most significant situation that followed the devastating 2005 Hurricane Katrina was the discovery that the racial geography of the city had remained unchanged since its racial segregation eras. As the gushing winds and high waters of the hurricane tore through New Orleans, disembowelled abodes of the city's black community could not but expose the concealed ghosts of segregation and slavery: poverty and misery.

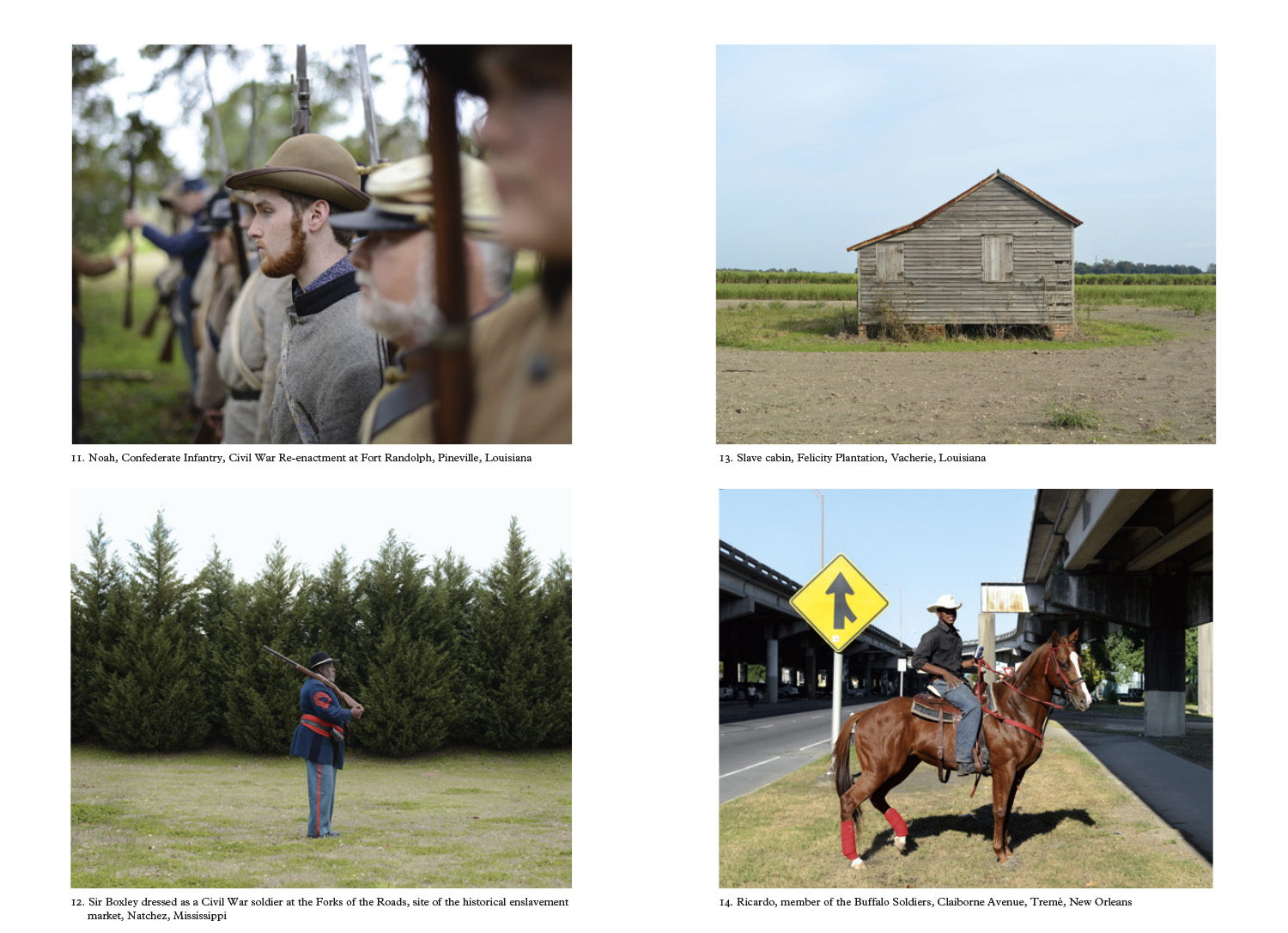

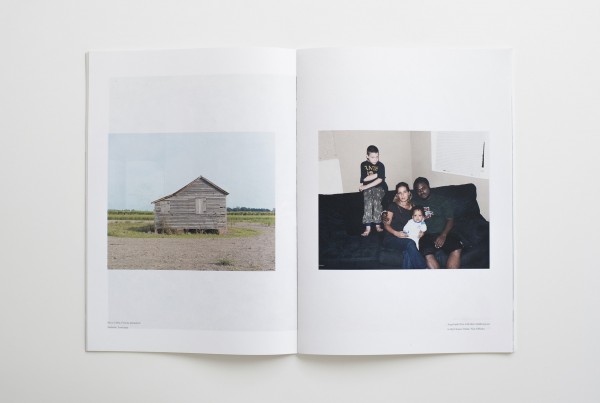

It is with this depiction of the situation at hand that I decided to undertake a research documentary project in Louisiana and Mississippi, to better understand the origin of this racialised geography. I also sought to wrap my brains around how the various racial categories shape memory, geographical heritage and economic, political and interpersonal relations.

The series presented here was undertaken in Louisiana and Mississippi, two former confederate states that share a common history: French colonisation, slavery and plantation economies, civil war trauma, reconstruction, segregation, economic decline and a recent redirection of the economy towards mass tourism.

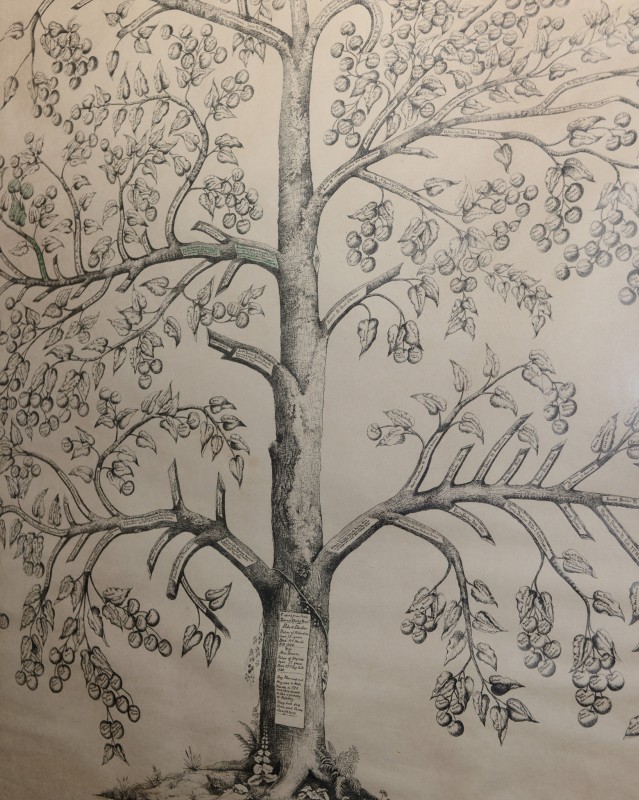

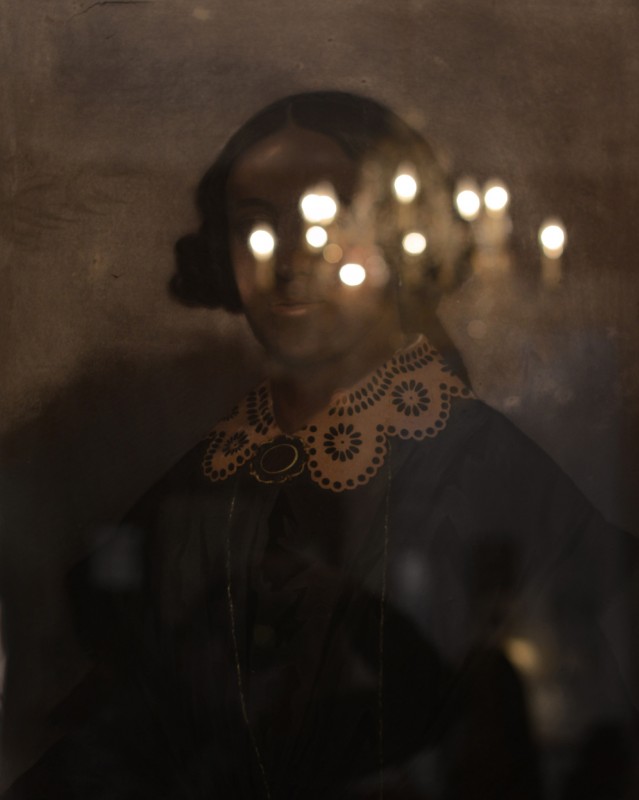

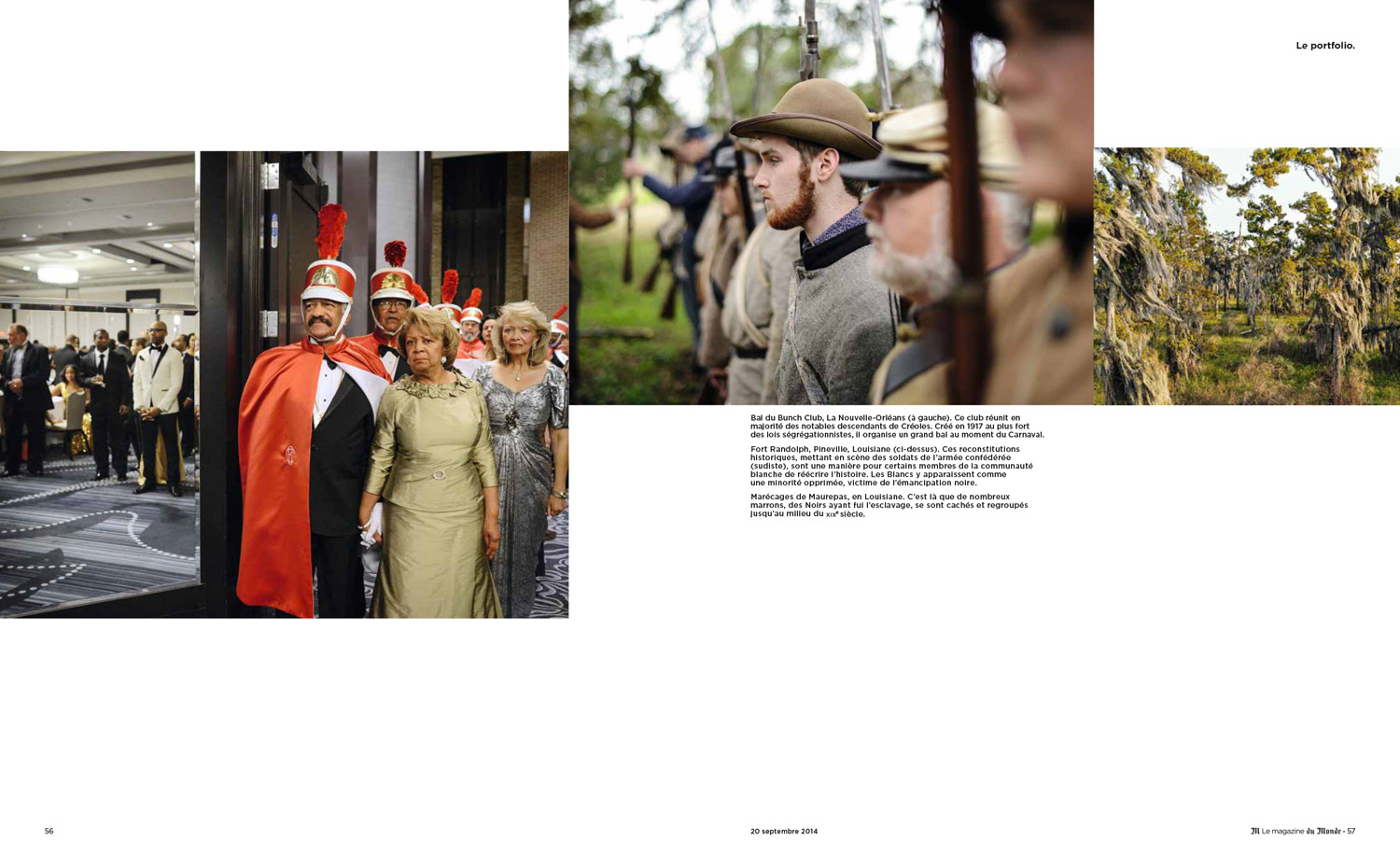

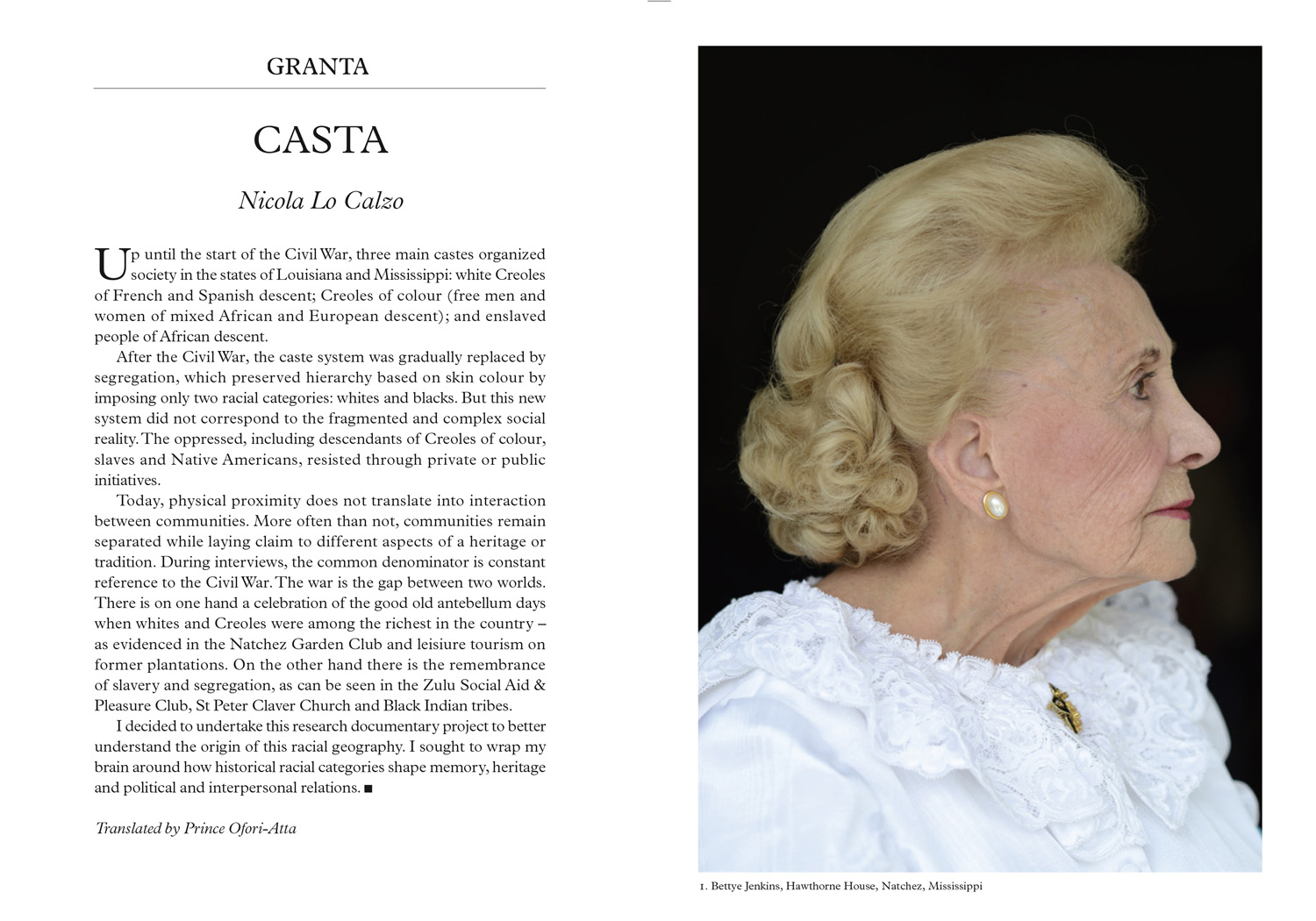

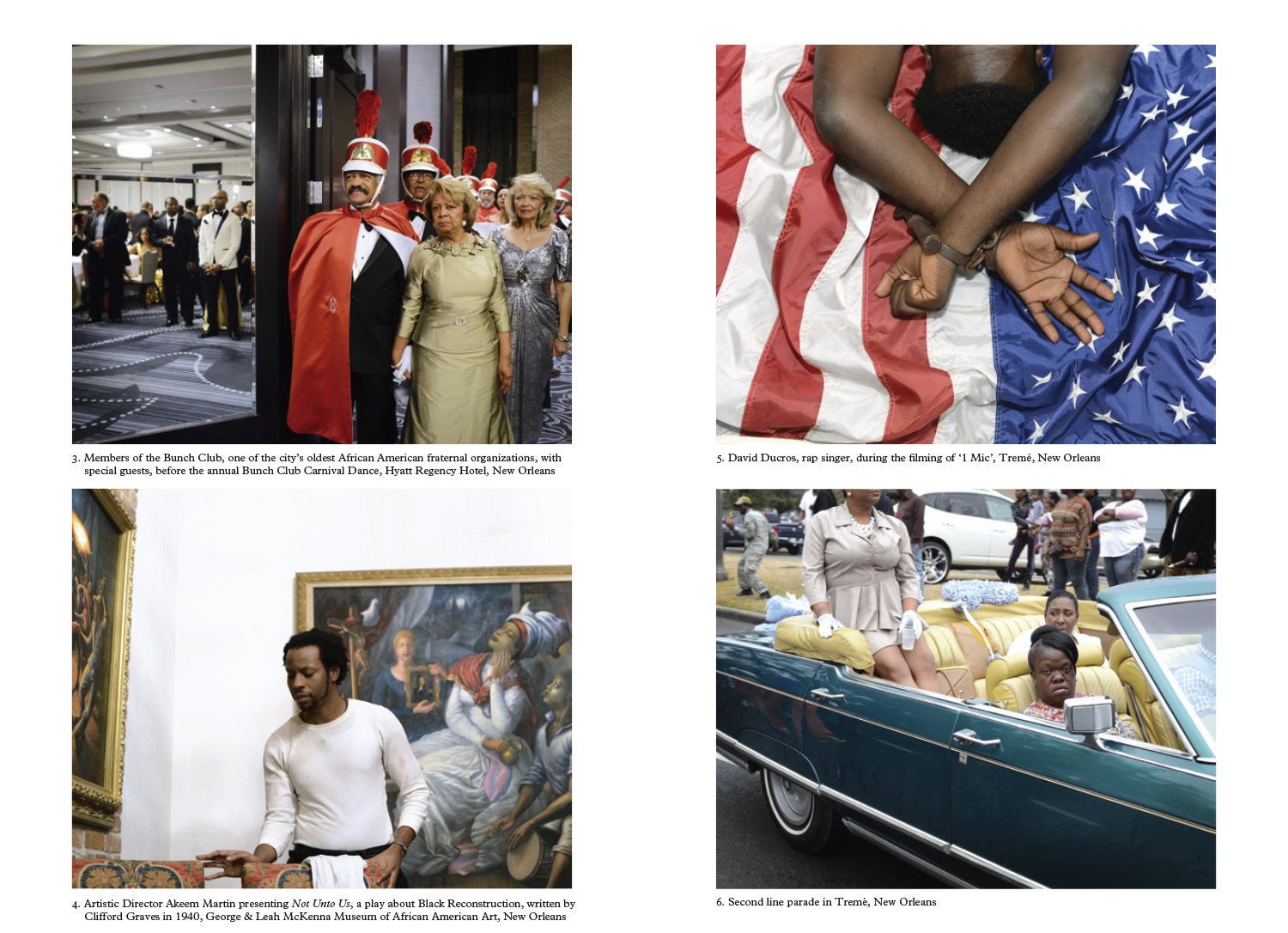

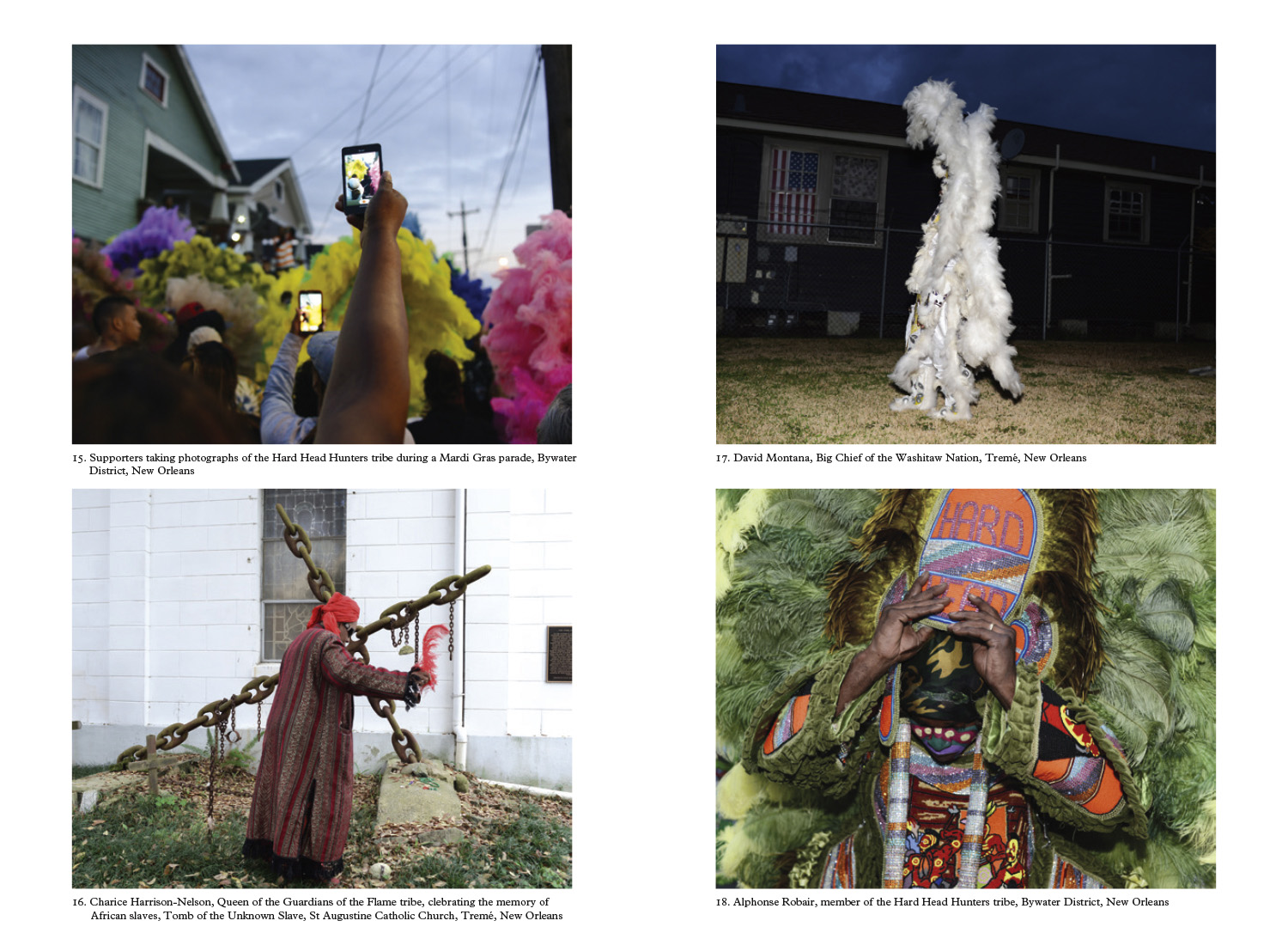

Three of the most established communities in these territories appear in this study: Black, Creole and White. I, especially, tried to question real memories linked to the Antebellum (which preceded the American civil war and Black emancipation) and segregation periods by examining certain modern modes of memory transmission and the re-appropriation of past events.

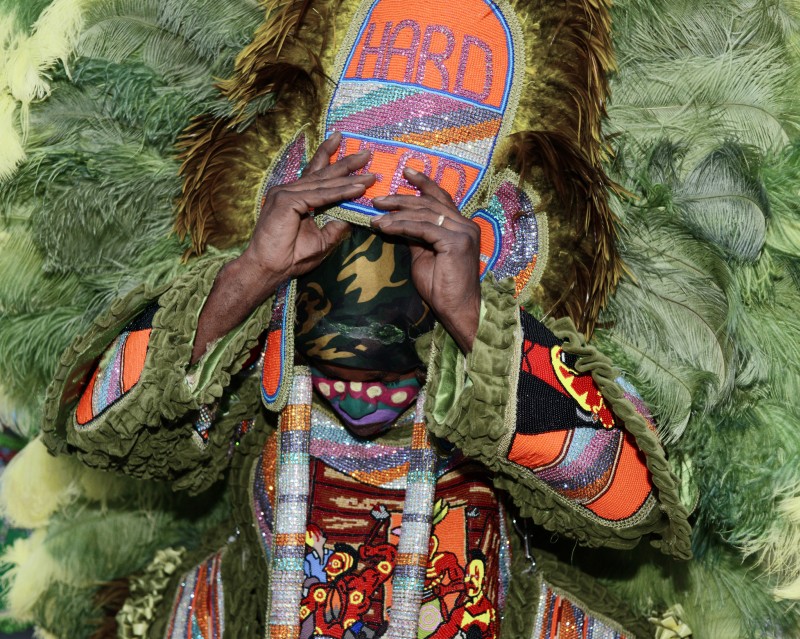

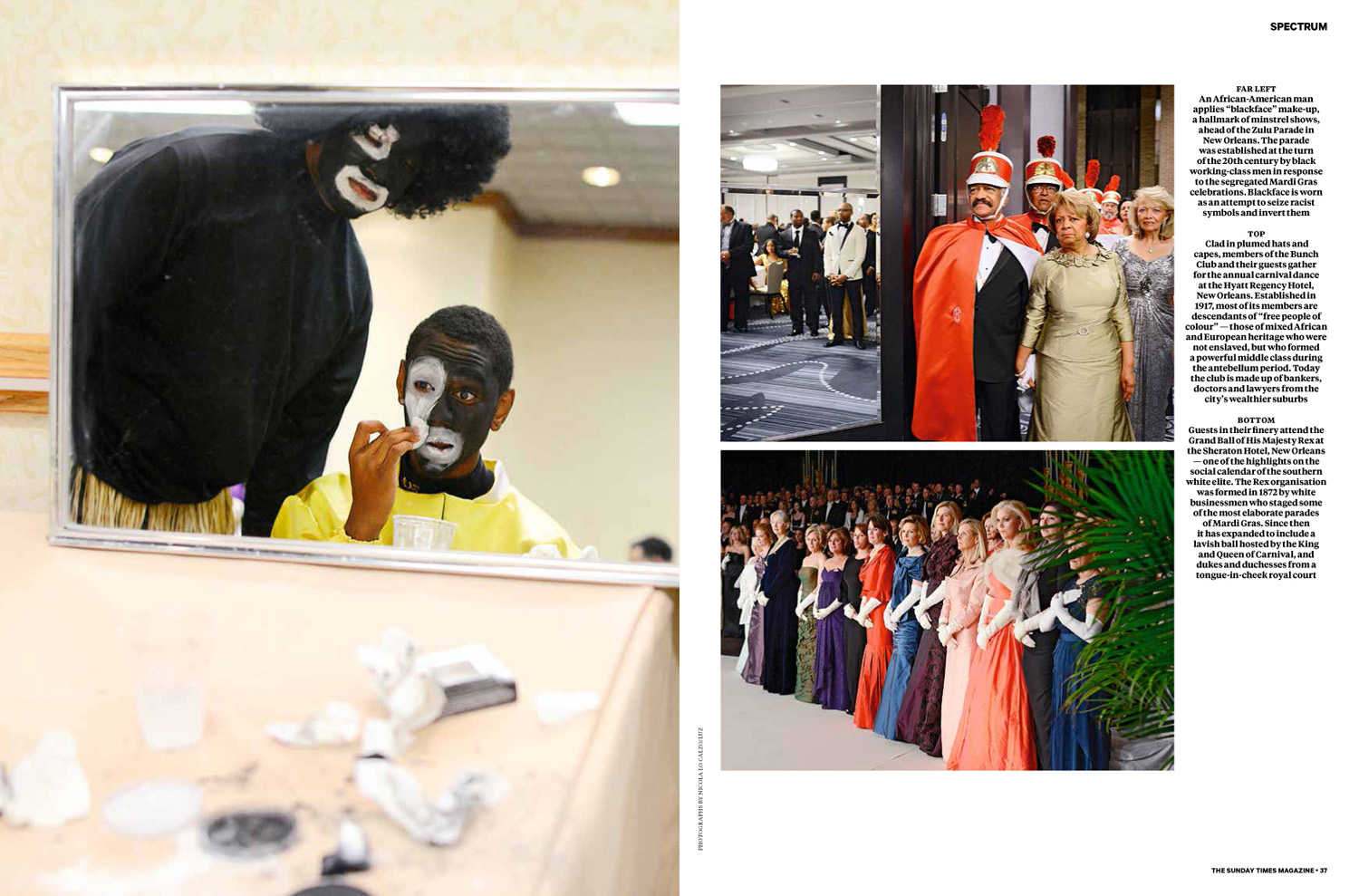

The common denominator in the speeches and testimonies among people of these different communities, during interviews, is seemingly their constant references to the American civil war. The war, to them, is the gap between two worlds. While there is on the one hand the remembrance of slavery, which is vital to the African American narrative (see the activities carried out by the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club, St Peter Claver church, Black Indians tribes, etc), there is on the other hand a celebration of the good old Antebellum days when Louisiana's White and Creole communities were among the richest in the country (as witnessed by virtue of Natchez Garden Club's activities, leisure tourism on former plantations and the enactments of the civil war).

The photographs, produced within a six-month research period (2013-2014), seek to explore the complexities and contradictions linked to collective memory in the southern parts of the United States, an area that has been affected by social injustice and racial discrimination. The project examines how and why the communities re-appropriate the past, the thought process among its racial strata and the ways and manners by which they are transferring this memory to the next generation.

Nicola Lo Calzo