Mas : Slavery Past Heritage in the French West Indies

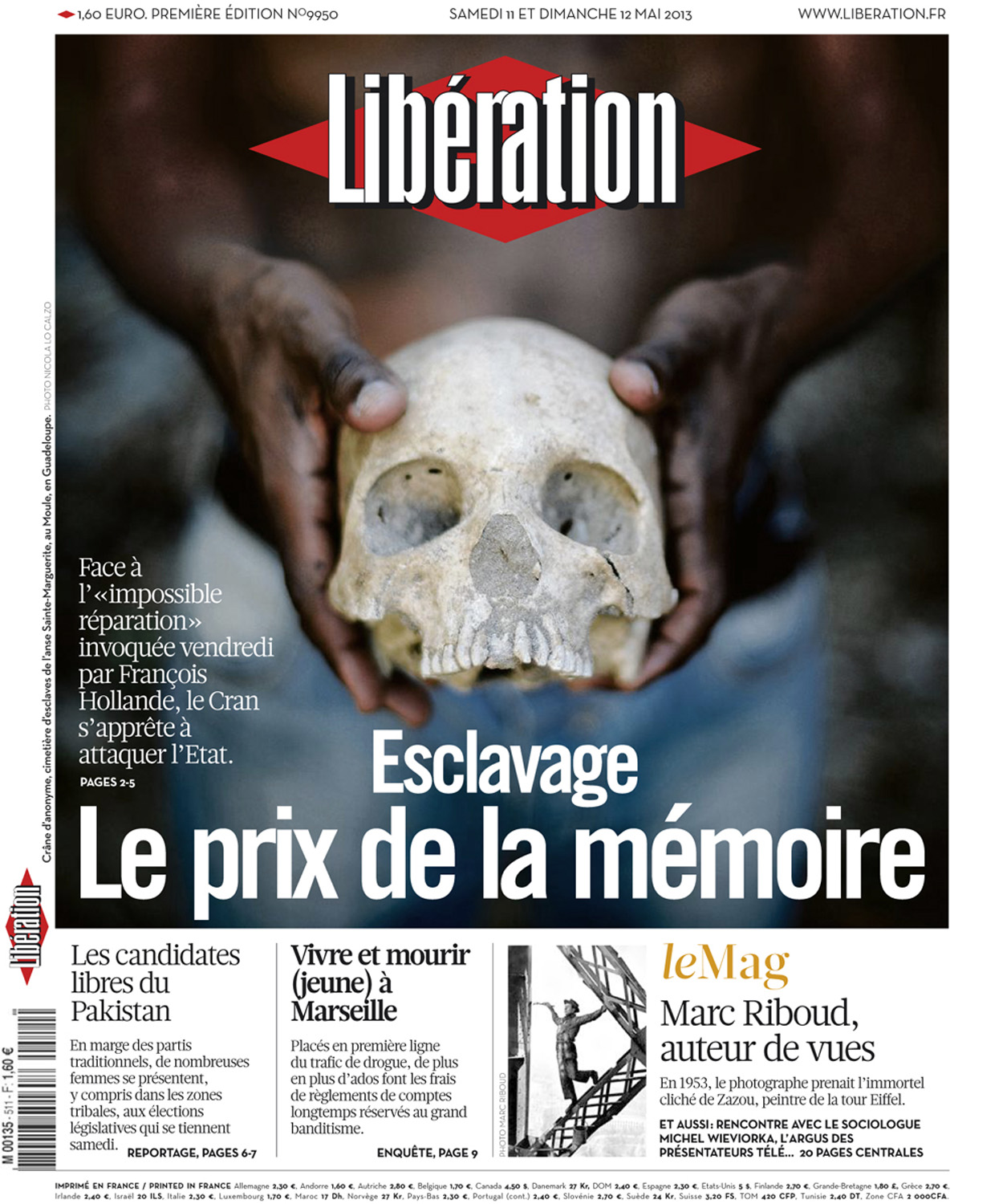

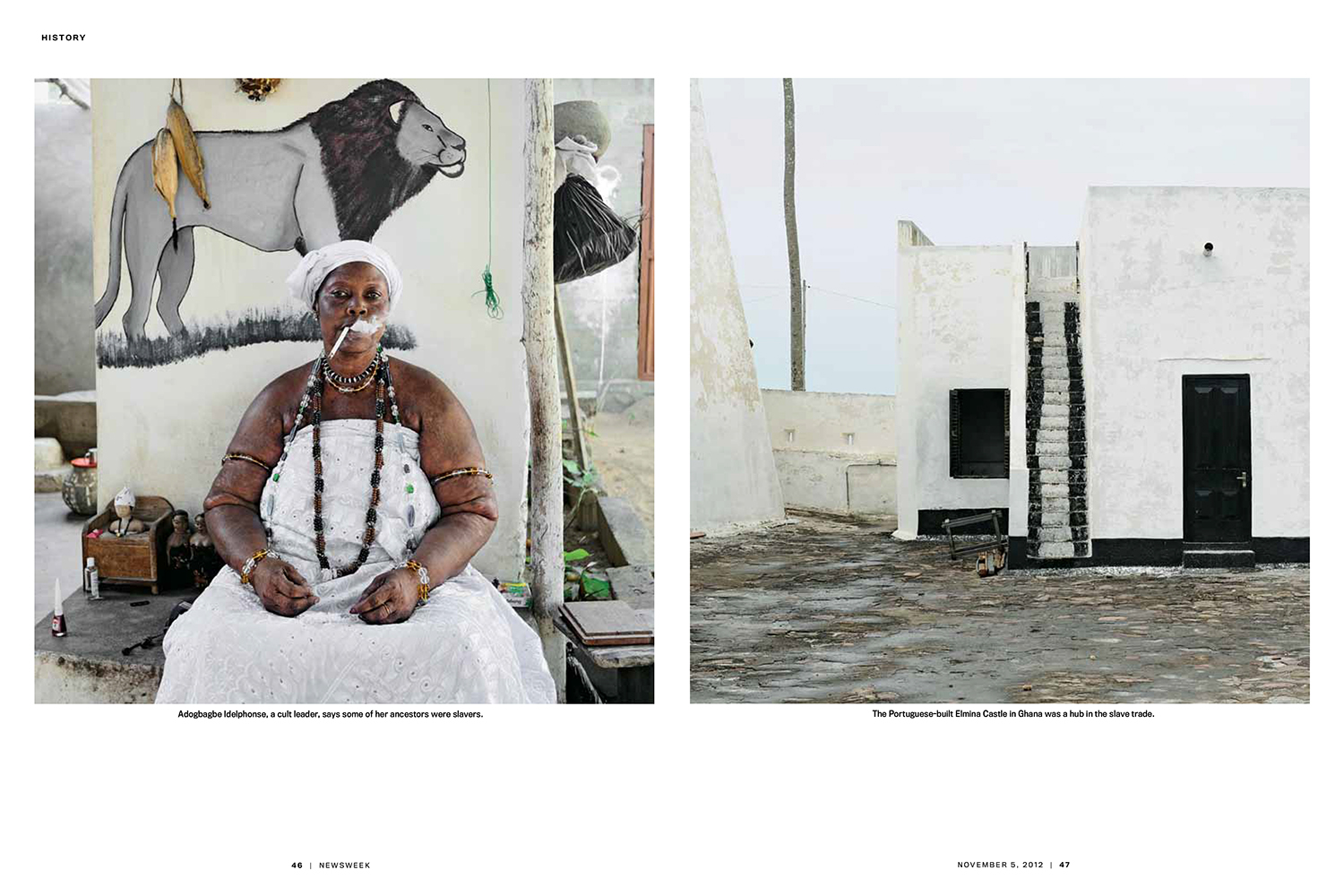

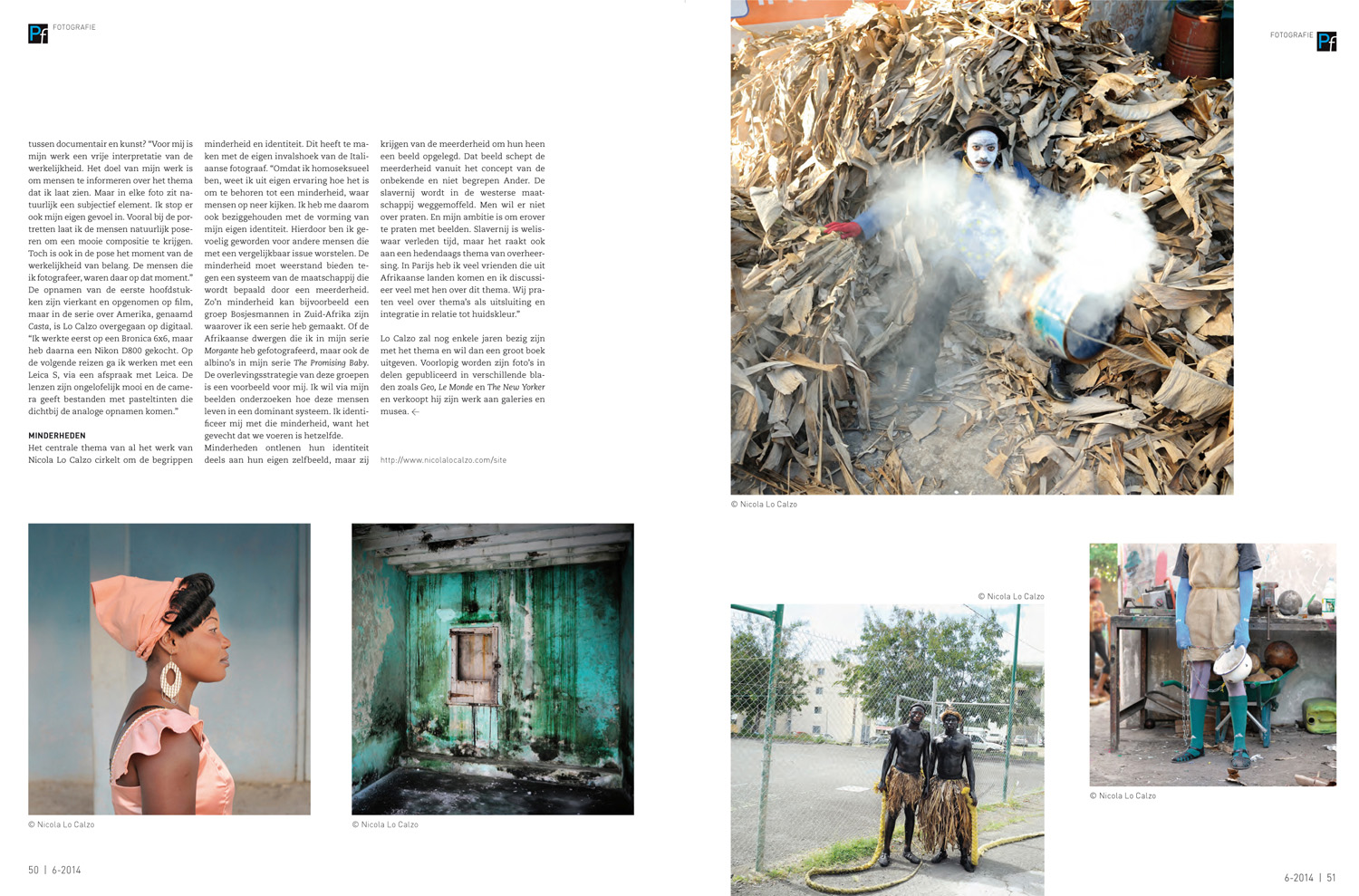

The history of the French Antilles is linked to the European colonization and the colonial slavery, which the Spanish, the English, the French and the Dutch practiced for three centuries. Especially in Guadeloupe, slavery remains one of the founding acts of the society. After the abolition of slavery in 1848, the French monarchy, and then the new French Republic, made every effort to ensure that the new citizens of the French Antilles forgot their past linked to slavery. The education system played a major role in that action and benefited from the fact that the slaves’ descendants were hung-up by their origins. Since 1970, a process of reconstruction of the lost memory is taking place, as well as a reappropriation of the French antilles historical heritage.

The notion of a Guadelupian identity seems to be indivisible from the commemoration of a collective slavery history, which is re-appropriated and transcribed from iconic events and figures, that are essentially chosen to symbolize the popular resistance to colonization. In Guadeloupe and the French Antilles, the “rupture of parentage” caused by slavery was followed by a voluntary or forced oblivion of the individual and collective memory.

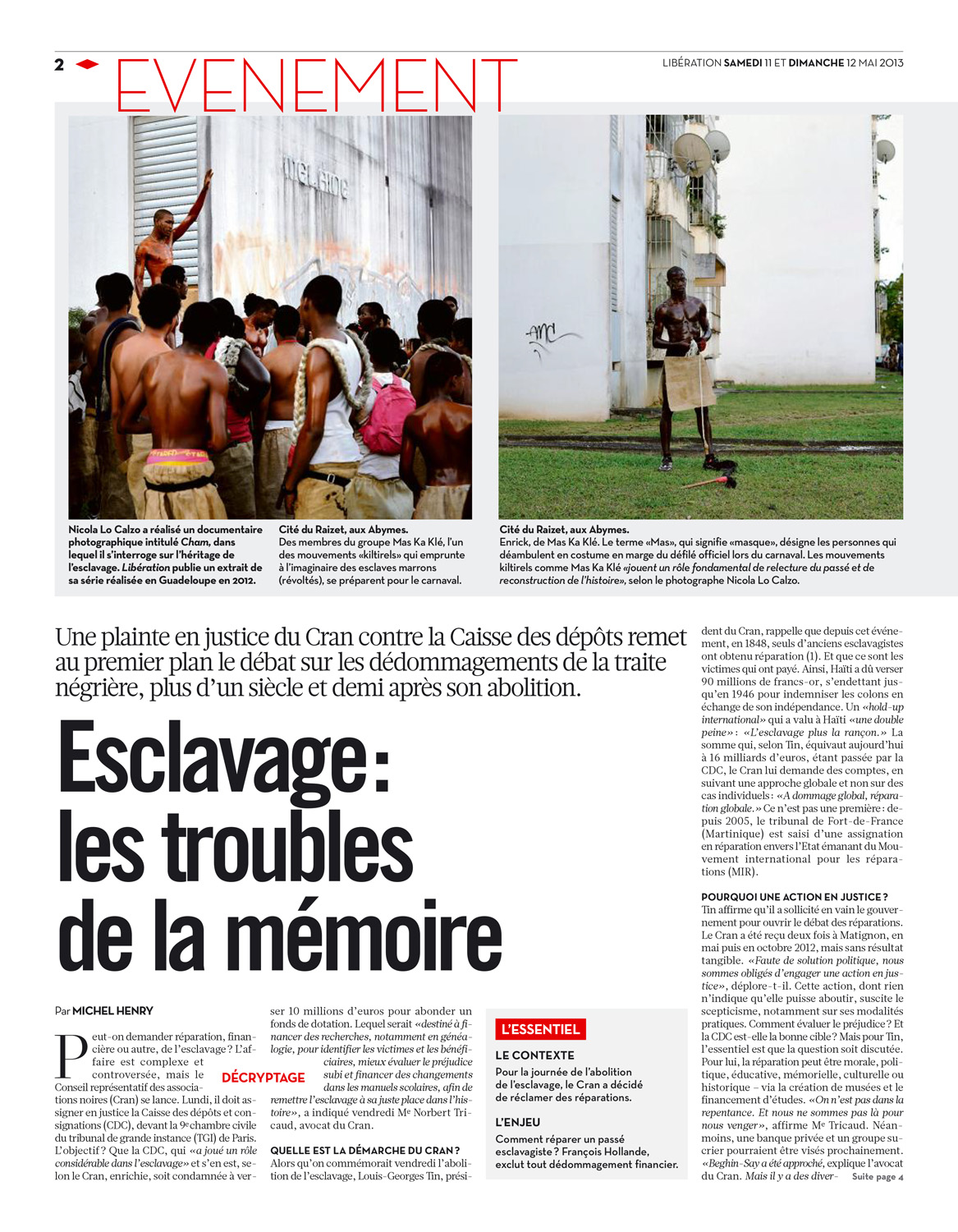

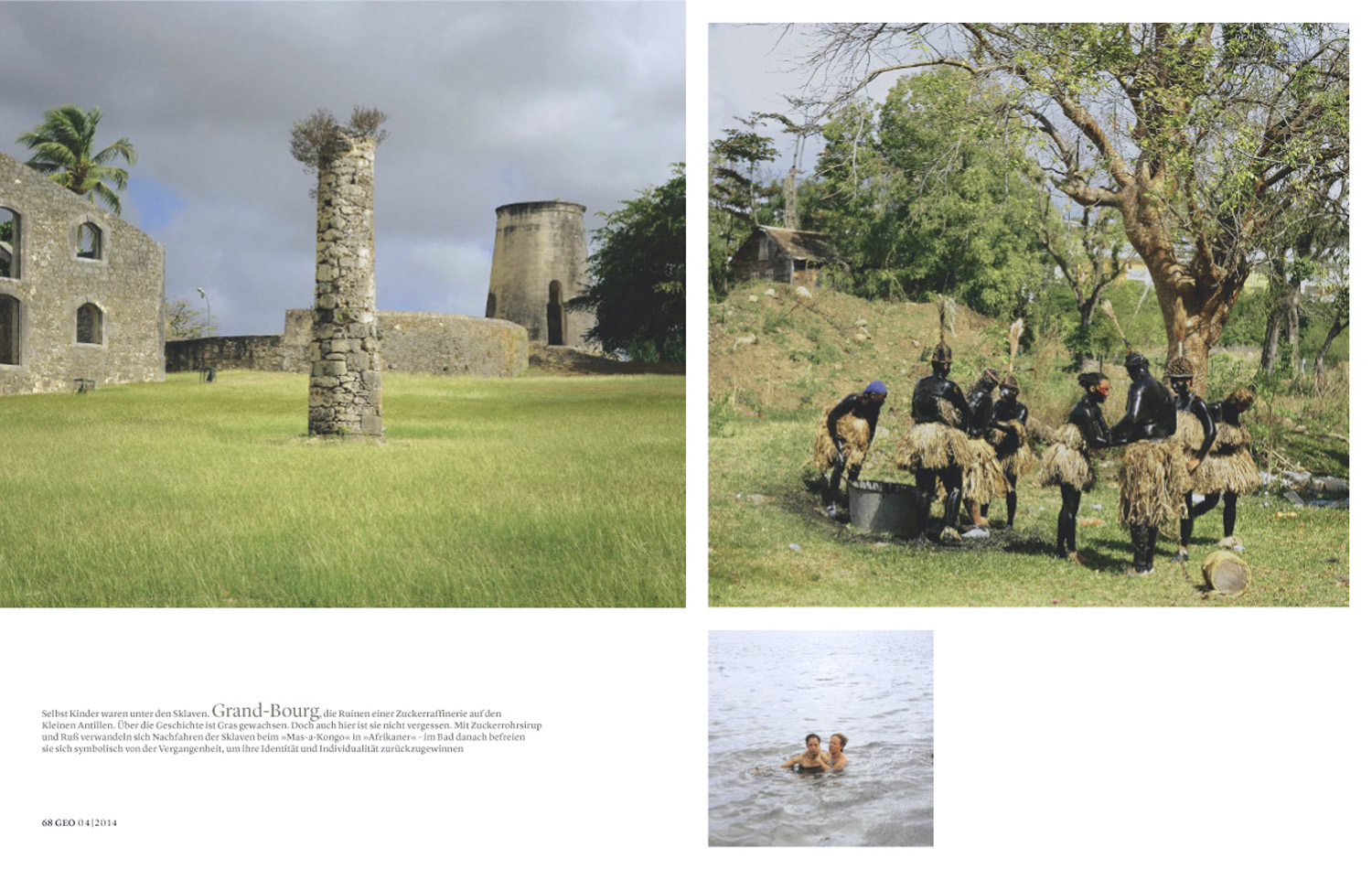

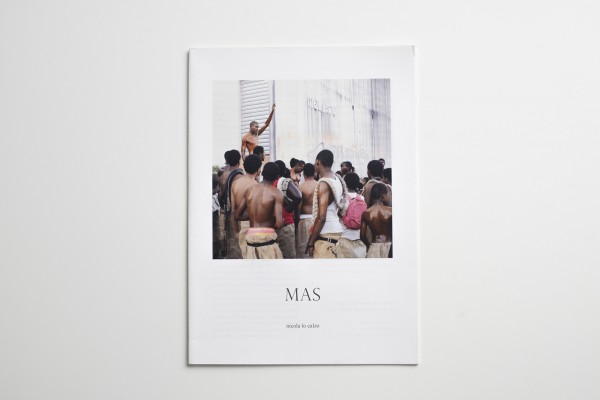

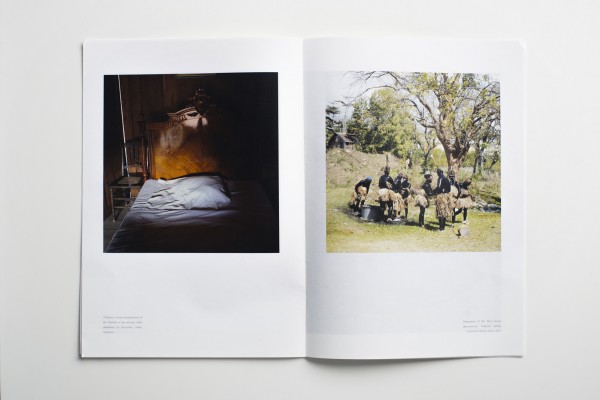

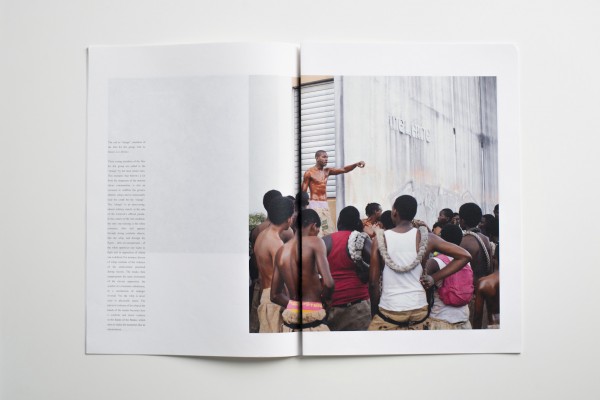

Nowadays in Guadeloupe, the slavery memory goes mainly through the re-appropriation, or even the discovery of the past, through genealogy studies and the discourse carried by the movements kiltirel. The movements kiltirel or «Mas groups» - «Mask groups» in English - associated with the carnival, play a fundamental role in the recollection of the past and the reconstruction of the history. These groups, the most important being Voukoum (literally noise), Akiyo and Mas Ka Klé, have been working for 30 years to revive the symbols of the black resistance, through the developing of the Mas tradition. These groups, born in the Seventies, are linked to the movement of secession LKP and they are promoters of a political and ideological discourse. They chose to present a particular vision of the Creole society, by insisting on its link to the times of slavery but also by erasing the figure of the white man, which would stain the idea of the original purity.

It is a chosen vision, a selective historical memory. It is clear that the Creole culture was formed over the course of different contributions: European and African, but also Caribbean, Indian and American. The photographic essay (2012) shows the acuity of the slavery problem in Guadeloupe. There is little doubt that this event in the West Indian history is not a closed wound. The result of this research shows that slavery, far from being obliterated from the Caribbean memories, appears as a key period, sometimes occulted, sometimes rehabilitated, sometimes reinterpreted, and that really determines the relationship of the Guadeloupe citizens towards historical times. In that sense, the Guadelupian carnival has become a place of dramatization of the identity and heritage, and proposes a local reconstruction of history and its heroes. The Carnival appears as a central issue of the various cultural and identity policies.

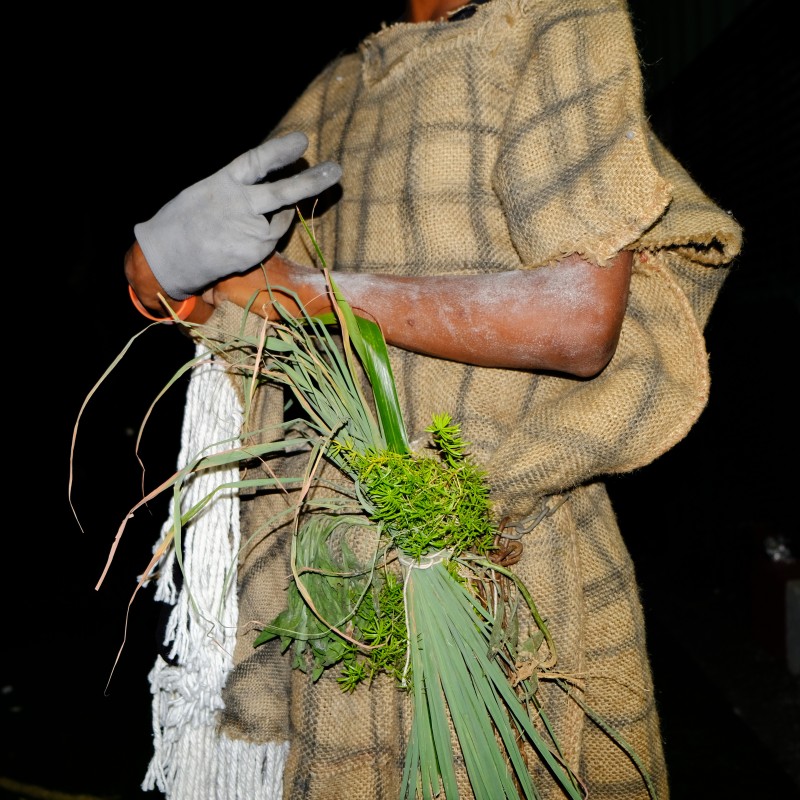

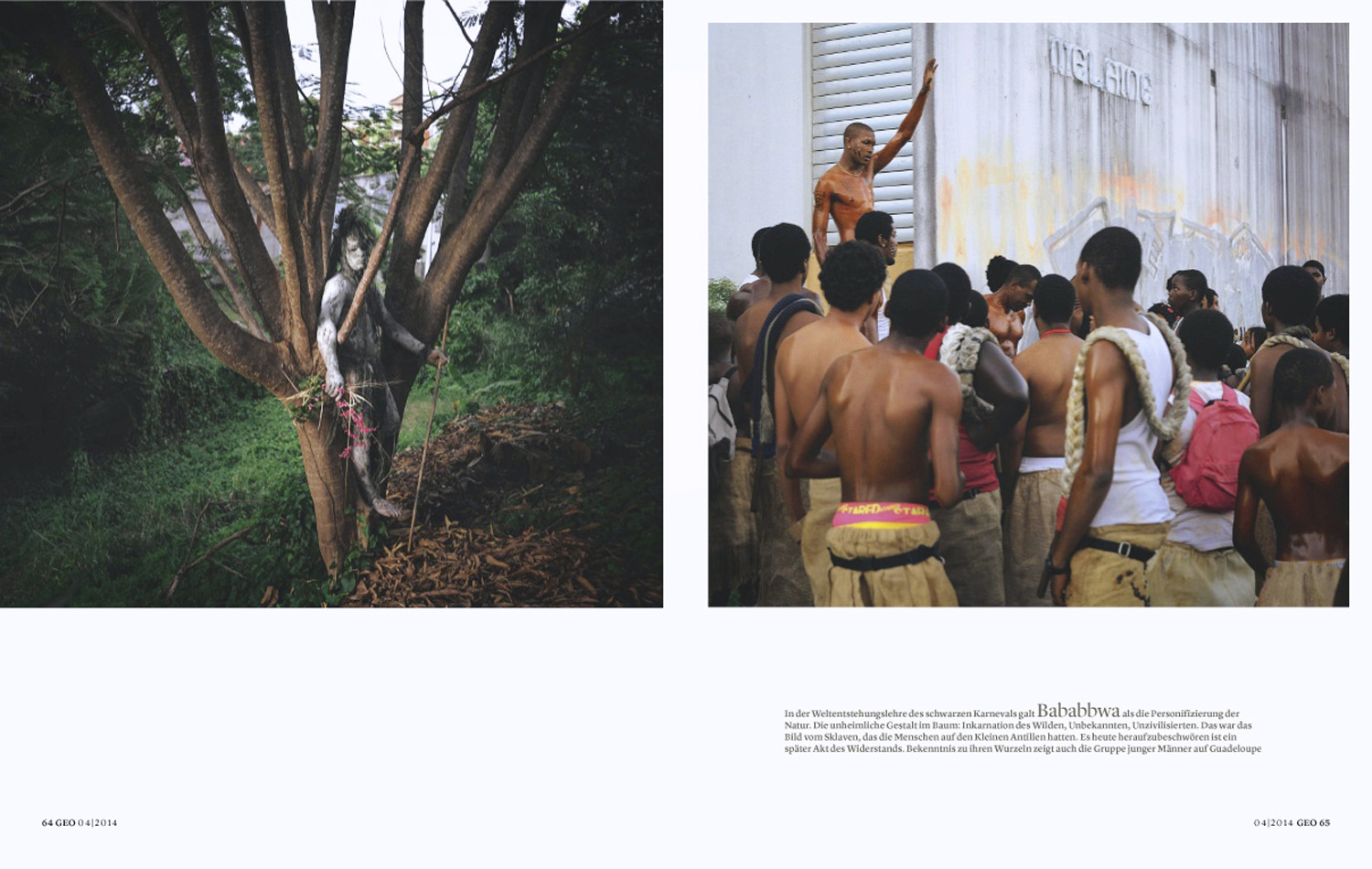

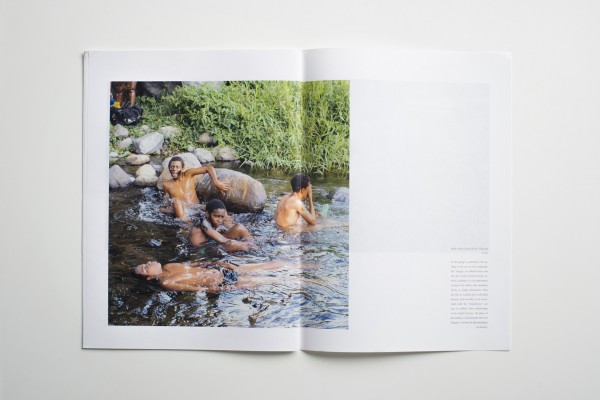

In this context, the mask groups propose a re-appropriation of certain elements of the cultural heritage, through a recollection of the past. The Mas are traditional elements of the Carnival, the symbols of disorder, linked to rural areas, the world of nature, of the earth and forest. It is the world of the maroon slaves, at the outskirts of society, a world at the fringe, outlawed. Whenever the Mas looms from the countryside to invade the frightened city, it carries the popular representations that systematically associate it to the savage, “uncivilized” men, the “maroon slave”, from whom it wants to keep the rebellious and defiant behavior.

When they bring the Mas in town, these groups make an important transfer, since they push out a rural and popular culture that had to trick the colonial morality to survive, from the shadows and the night, to project it into the city lights. This symbolic shifting carries a huge emotional charge, since the Mas convey the wounds of a history as violent as its denial.